Success is a Choice.

We often hear the adage, "The path to success starts with choosing to succeed," as if it is through our very own choices that we succeed or have yet to succeed. While apparently wise and profound, we the audience are still left wanting. What does it mean, to "choose to succeed?" Is that not like a master chef telling us the key to success is to "love the food?" Or an Olympic swimmer telling us "to just keep swimming." On the one hand, perhaps they are telling us that there is no secret keyword passphrase to success and that anyone can do it. Or perhaps they are just saying that they can do it but are unwilling or unable to prove how they did. But for the rest of us, what is it we can do exactly to succeed? Where is the "Success for Dummies?"

The scope of this paper focuses on management success - AKA building and managing a dream team of great team members. For employees not yet as managers, learning how to manage is the surefire proof that they are ready for promotion. For managers who have not yet learned the tools of successful team building, it is not too soon to set this up.

For too many of us managers, the quest to fill out a team with great members is an expensive, time and labor intensive, and often frustrating endeavor. Speaking over the years with heads of Human Resources and Recruitment, we often find the general sentiment to be one geared towards finding the right person for the job. As team member duties seemingly grow more complex and buried in the minutiae of skill details, it becomes harder and rarer to find a perfect match. It becomes as if our requirements were, "someone 6 foot and 1 half inch tall, with dark hazel eyes, pupils nominally at 2.3 mm with a standard deviation of 0.25, hair trimmed and Argan-oil infused, wears Gucci shoes and Tissot watches, reads Shakespeare, has a voice timbre code of 1542x, and is named Prince so-and-so…" Not only is this what anyone else would call close-minded, it leads to a very long, very deep search. In business terms, this means "expensive." As businesses change in a seemingly ever-changing world, these requirements expire quickly, only to be replaced with yet more close-minded lists of requirements.

Such requirements as these, by the way, are drivers for deep search technology companies. Technophiles view this as a mutually beneficial arrangement. From a business perspective, however, the search companies are taking your funds and grooming you as their lifelong customer. "Measure twice and cut once" the adage goes. This means spending some time to set your goal rather spending time blindly stumbling into the ill-defined unknown. Otherwise, it feels like hard work and progress, but it is actually very wasteful.

The goal in building and managing a great team member lies in defining what is a great team member.

Earlier papers defined a great team member (employee, manager, etc.) as the following:

One who SEES what needs to be done, does it, and SEES unforeseen opportunities.

A different perspective could run like this:

Or one who SAYS what needs to be done, does it, and SAYS unforeseen opportunities.

Or even this:

Or one who HEARS what needs to be done, does it, and HEARS unforeseen opportunities.

The base concept as discussed earlier is someone who connects with us and grows. That growth carries the team forward. That growth is directly related to defining the heretofore un- quantifiable intelligence.

But in this paper, the meta concept is the idea of choice. Our choice of word biases us on what to seek. Ergo, if we do not seek it, we cannot find it.

What we choose to seek is the key. This is selective attention, the locus of which is in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This is the region responsible for such famous tests as the basketball test. In popular culture, it is responsible for Homer Simpson, who sought a dropped peanut but found - and initially discarded - a $20 bill.

Choosing the appropriate metric allows us to turn previously unsuitable members into great team members. Deciding on the appropriate metric follows much the same approach as in counseling. The patient rambles on about this feeling and that complaint. There may be a long litany of requirements. Perhaps they might even say something like this:

"I need someone 6 foot and 1 half inch tall, with dark hazel eyes, pupils nominally at 2.3 mm with a standard deviation of 0.25, hair trimmed and Argan-oil infused, wears Gucci shoes and Tissot watches, reads Shakespeare, has a voice timbre code of 1542x, and is named Prince so-and-so…"

The good counselor or analyst knows not to take everything literally, but to direct questions in response. To translate the situation into suitably actionable terms. What is the general trend? What is the forest behind the trees? Perhaps in the above scenario, they need someone tall and handsome and educated. Whose characteristics make them confident. Perhaps in the above scenario, they need someone confident. While the above litany of overly specific requirements may shift from "6 foot and 1 half inch tall…" to "6 foot and zero inch tall…" necessitating a return to the drawing board, the big picture "confident" that captures the requirement elegantly remains constant.

That constancy increases the pool of candidates. The increased pool decreases cost. The constancy is appropriate for both short and long term. With requirements stated in elegant terms, the seemingly ever-changing world turns out to be remarkably constant after all.

This is not a profoundly novel concept. In evolutionary biology, there is the concept of "adaptive peaks." A dinosaur evolved over millions of years to be an apex consumer - eating vegetables while fending off other dinosaurs, say. But after an asteroid strike and global conflagration, a new set of animals evolved into equally apex consumers - eating other animals while fending off rivals, say. The more the world changes, the more it stays the same.

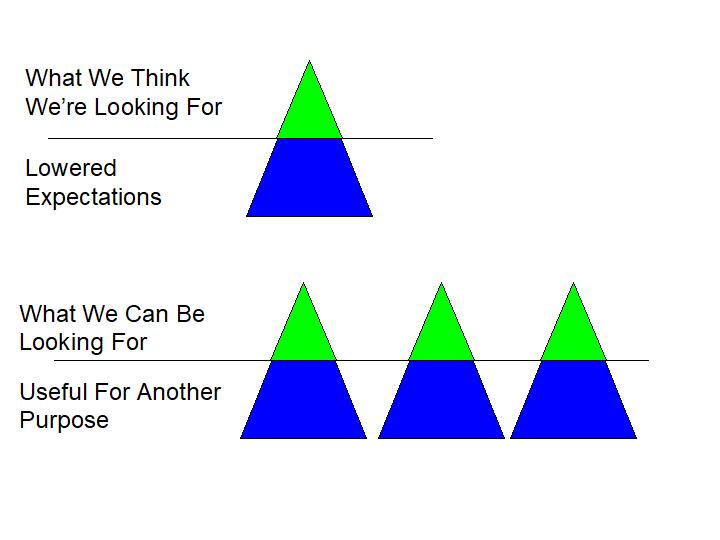

These are not lowered expectations or a lesser selective process in any way. An apex consumer is an apex consumer. There are multiple approaches to achieving equivalent apices. What defines their underlying form can be surprisingly constant under the appropriate perspective. What matters is the choice of perspective.

We can waste untold labor hours and shockingly high search fees to find the exact great employee we had in mind on a whim. Or we can spend some time looking not at the candidates but at ourselves and what exactly we do and need to be great team members. It is not a great mark of management in having won the lottery and finding the one perfect team member in a million. If that were the case, we wish them good luck in repeating the process to scale up their success.

It is a mark of great management in understanding what exactly management means and how to recreate it: faster, better, and cheaper. It is a mark of great management in finding any among the millions and being able to fit them to the essentials of great team membership. Those teams need no luck to scale up their success. They already have the formula. It is the poor manager who spends their effort enforcing their own perspective of greatness. A great manager continually seeks out and learns to reconcile new perspectives. Again, this is neither novel nor avant-garde. This is merely Piagettian Assimilation-Accommodation and most importantly, the Equilibration that reconciles growth and development. (Siegler & Alibali, 2005)

Neurological research shows the same underlying assumption bias. Colloquially, a great team member is smart and has a "large memory capacity" with which to learn quickly. While we are currently unable to even evaluate what it means to enhance memory capacity - humans are not computers possessing RAM chips - neuro-medicine research often starts with restoring memory losses.

Le Douce, et al (2020, Impairment of Glycolysis-Derived l-Serine Production in Astrocytes Contributes to Cognitive Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Metabolism, 2020; 31 (3): 503) discuss how astrocytes (a star-shaped glial cell, with "astro" having the same root as "astronaut") convert L-serine into D-serine. The D-serine stimulates NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors. NMDA receptors are directly gated glutamate receptors that stimulate Hebb-style neural connections. In short, they react to memories to better store them. Their mice models showed that starving them of L-serine causes loss in D-serine, which causes loss in NMDA ability, which causes loss in memory function. Their conclusion is that eating more L-serine can at least restore memory function. Their implication is that gorging on L-serine could potentially enhance memory capacity.

Ryan, et al (2020, Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the effects of aspirin on dementia and cognitive decline. Neurology, 2020; 10.1212) explore the anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin, a known treatment for heart disease, for potential benefits in treating Alzheimer's Disease or dementia. They used a randomized, controlled trial of nearly 20,000 patients over 5 years. They found no significant effects. Adding that the patients might have been too healthy belies the implication that there are limits to what we can do to enhance beyond a healthy baseline. Perhaps we are already optimized when at full health.

Cheval, et al (2020, Relationship between decline in cognitive resources and physical activity. Health Psychology, 202) explore non-drug treatments for cognitive decline. They tested over 100,000 patients aged 50-90 over a 12 year period. Their battery of cognitive exams included such tasks as naming as many animals as possible in 60 seconds, or recalling a list of 10 words after a timed delay. Their findings reversed the commonly held belief that exercise prevents memory loss. Rather, it appears that memory loss predicted lack of exercise.

As the above research sample shows, our research into reversing memory decline serves as proxy for our hope to enhance normal memory function. The underlying bias is that we can or even should be working on memory capacity function. That there exists some compound we can take or procedure we can do to help us to remember faster or with greater fidelity. That we should be akin to our own computers. But we forget that we built those very computers to do a task without understanding what it is that we ourselves do.

Westbrook, et al (2020, Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work. Science) explored a fascinating angle with Ritalin and Adderall. The common belief is that Ritalin helps people better focus and become more effective. In their study, 50 adults aged 18-43 each took a placebo, ran through a battery of tests, then took a generic Ritalin before running through more tests. The experiment was double blind, though longitudinally controlled. Their findings confirmed that Ritalin increases the dopamine levels in the striatum. This increases motivation - but not focusing ability. In short, if Ritalin and the like make us more effective, it's not from increased ability to focus. It is from increased willingness to try. It affects the choices we make, not the ability to carry out them out.

Thus, we can further define a great team member in this perspective as a protégé who chooses as we would. That is trust. That is connection. That is both the #1 and #2 primary factors in hiring great team members - per management best practice policies at Chase Bank, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, and others. Namely, can we trust the team and can they trust us. Together, this makes for great productivity.

Great team members come about not from finding the unknown, je-ne-sais-quoi-but-I'll-know-it-when-I-see-it. Great team members come about not from saying we choose to make them. Great team members do come about from understanding and explaining the choices we make so that others can follow in our footsteps to do the same.

Imagine a team member who knows what needs to be done, does it, and seeks out unforeseen opportunities to extend themselves - and in so doing, grows the group. That is a team member who does what we want, when we want, and without us asking for what we want. Why do we not need to ask them? Because they already know and choose as we would have. Why would they choose as we would? Because they see what choices we make to become manager and know that by doing the same, they become manager.

Great employees make great products.

Managers make great employees.

Great managers make more managers (and in so doing, become Executive Managers).

Armed with this appropriate perspective, the search for great team members has little to do with deep search or broad search outside for the perfect candidate. It has little to do with expensive, exhaustive, and classified interviews. It has little to do with competitive vanity projects as if to say, "only the arbitrarily select few with this long list of requirements can do what I do." Rather, it starts with choices - from within. Our very own business choices form the requirements. This is our factory process. And like with any great factory process, it is the process itself that makes a product great, not so much the raw material.